It was an ordinary Saturday when seventeen-year-old Anna Schumacher asked her mother for permission to visit her father’s and sister’s graves on August 7, 1909. The young woman wanted to place flowers on them at Holy Sepulcher Cemetery, which was a few miles from her home on Cady Street in Rochester. Anna wasn’t accustomed to traveling alone, but had visited the cemetery by herself three times before. Permission was granted, and she and a friend boarded a streetcar after lunch. The friend, however, was going on to Charlotte and left Anna on her own at the stop near the cemetery. This is the last time Anna’s friend saw her alive.

When Anna didn’t return home by evening, her mother and siblings became quite concerned, as it was out of character for the young woman. The Schumachers were a close Catholic family; their mother was widowed in 1897, and the children took on responsibilities early. Even at her young age, Anna had regular employment as a seamstress at Michael Sterns & Company. The teenager hadn’t ever given her mother cause for worry until now.

When Anna still wasn’t home by 10:00pm, the family went to the Bronson Avenue police station to report her missing. The officer at the desk dismissed their worries, telling them it wasn’t odd for a young lady to be out late and that it was safe for her to walk anywhere in Rochester. The family left in disgust, telling the officer that Anna wasn’t one to stay out late. They went home to gather lanterns and searched the cemetery near the family gravesites until the wee hours.

Finally ending the cemetery search, the family reported the disappearance to Rochester Police Headquarters on Exchange Street at around 2:00 Sunday morning. Although the officer was more sympathetic, he informed the family that the incident was outside their jurisdiction and asked them to let the station know if she didn’t turn up by 9:00am.

A search party of fifteen, organized by one of the Schumachers, began looking for Anna again when the sun rose on Sunday morning. The family was now desperate to find her. They started a house-to-house search near the cemetery with no luck, but one man who answered the door advised them to contact Constable Baker of Greece to help them search for Anna. He said there was no one like Constable Baker to find a missing person. By this time, the Rochester Police and the Monroe County Sheriff were also involved, and the sheriff had asked for every available officer to search for the missing teenager.

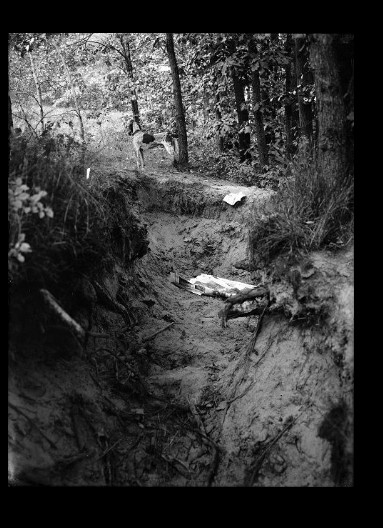

Constables Stalhan Baker and Otto Friedman carefully covered the cemetery’s outer boundaries without success, and the family endured another night of not knowing if Anna was alive or dead. On Monday morning, August 9, the constables joined Anna’s brother, John, to continue the search through the extensive undergrowth that edged the southeastern section of the cemetery down toward the Genesee River. While the constables pushed their way through bushes and brambles, a noise caught the attention of Constable Baker. Curious, the men followed the scrambling noises and found a path leading closer to the river. It was there that the marks of something being dragged over the ground were visible. The marks led them to an area where a woodchuck hole had been dug around, and as the men stood and looked at the sandy soil, they realized a grave had been recently dug. Constable Baker began digging with his bare hands, discovering that loose sod had been laid across part of the grave. Minutes later, a piece of ribbon and a piece of fabric were visible. Constable Baker stopped, telling Friedman they needed to call Sheriff Gillette and the coroner to the scene.

A short time later, while John Schumacher, Jr., the sheriff, the coroner, and others watched cemetery workers carefully removed sod and sand from the grave, revealing the body of Anna Schumacher. She had been placed on her side with legs drawn up, her blouse ripped open, and terrible facial bruising visible. The autopsy later confirmed that she’d been raped, beaten, and then strangled. The violence of the attack and murder was horrifying. However, robbery didn’t seem to be part of the killer’s motivation. Anna’s small diamond ring, the money in her purse, and her return ticket were all accounted for. Anna’s personal effects had all been buried with her.

The sheriff immediately ordered all police officers to detain any suspicious-looking men, especially those with scratches on their faces or arms, since it was obvious that Anna had fought desperately for her life. Pieces of skin were recovered from under her fingernails.

Several transient men and locals who were known troublemakers were arrested and questioned, but ultimately released for lack of evidence. Wild theories from supposed witnesses told police they’d seen her following a man into the woods at the cemetery or that a woman in pink had lured her away. A man with scratches on his face and arms was arrested and aggressively questioned about his whereabouts on the fateful Saturday until his alibi was confirmed. All leads were dead ends.

A $2,500 reward was offered by the sheriff to bring the killer to justice, and two women came forward with odd stories of that Saturday afternoon in Holy Sepulcher. One observed a man in a dark suit, and the other woman noticed a man in a gray suit running from the cemetery. Both men seemed interested in unaccompanied women tending graves, but neither woman could identify them or provide any further information. Witnesses had also seen Anna trimming grass around the family graves, but she’d been alone. Workmen, who’d been repairing water lines that day as well, couldn’t recall seeing the girl, and no one heard Anna being attacked.

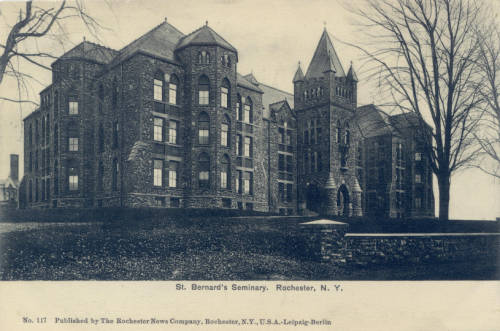

However, John Schumacher, Jr., stated that he’d seen a professor from St. Bernard’s Seminary at the pumphouse in the cemetery during the search for Anna, and the man had held a shovel. Then Anna’s mother, Mary, told the press about her premonition of evil when her daughter hadn’t come home by Saturday evening. She also told them that Anna had talked about becoming a nun, and was sure Anna wouldn’t have ever gone off with a stranger, but could have been deceived by someone asking for help, by someone she knew, or a priest.

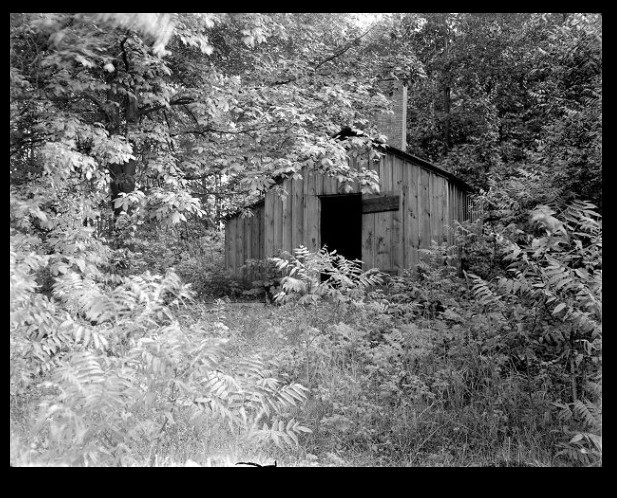

St. Bernard’s Seminary, a Roman Catholic school bordered Holy Sepulcher Cemetery. The campus, which had four Victorian Gothic buildings, opened its doors to train priests in 1893. It was situated on a 20-acre parcel that enjoyed spectacular views of the Genesee River. Police questioned the men who cared for the seminary’s livestock and farm; however, nothing new was learned from them to help identify the murderer. Whether students and faculty were ever closely questioned is unknown. The seminary closed in 1981 and is now used for senior housing.

By the end of August, suspects had been eliminated, and the sheriff remained frustrated in his efforts to find the killer of pretty Anna Schumacher. Suspicions about the cemetery workers and the seminary’s farm laborers lingered, but there was no evidence to link any of them to the murder. The murder scene hadn’t even been located, only the gravesite. The case was now cold, and the sheriff waited for a break to find the perpetrator.

In January 1910, the Monroe County District Attorney learned of a sailor imprisoned in New Hampshire who had confessed to the murder. His confession was lengthy, running to some 30 typewritten pages.

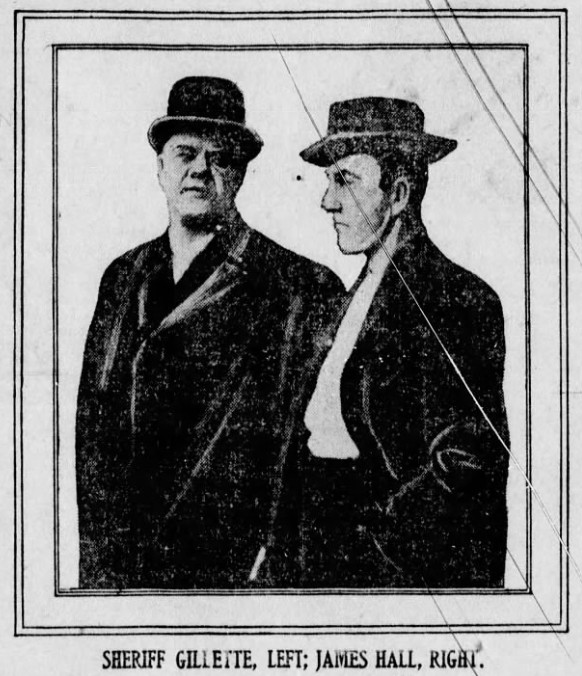

This sailor, James Hall, had been convicted of fraudulent enlistment into the U.S. Navy and was incarcerated on the prison ship, Southery, anchored at Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Hall told the district attorney and the sheriff that he’d been sleeping rough in the cemetery and panhandling food from nearby houses. That Saturday, he’d followed Anna after she left her father’s grave, and had only meant to stun her, but had accidentally killed her. Terrified of discovery, he dragged her and accidentally found a shallow grave that some boys must have dug. He then hastily shoveled sand over the body and fled. The district attorney, Howard Widener decided the story was plausible enough and worked with naval officials to have the man returned to Rochester to be questioned further.

On January 26, the prisoner was taken to Holy Sepulcher Cemetery to retrace his movements the day of the murder. Given a pack of cigarettes, James Hall looked around at the headstones and stated he’d never been there before. The shocked group of officials then took him to John Schumacher, Sr.’s grave and asked him if he recognized the headstone. Denying any knowledge of the area, he whistled a tune as if he couldn’t care less. Even when he was confronted with Anna’s shallow grave, he appeared not to have an interest in the proceedings and stated he’d never murdered anyone. The sheriff, who’d had custody of the man on the long train ride from New Hampshire, was out of patience, promptly returning him to a cell.

After a few more days of attempting to either confirm the confession or throw it out, Hall’s attorney, Mr. Brickner, finally was able to produce an alibi for his client that put an end to any hope of a grand jury’s indictment for murder. The sheriff and district attorney were heartily sick of Mr. Hall, who’d led them on a merry chase and left them in an embarrassing legal quandary. James Hall had enjoyed the hospitality of Monroe County and a break from the brig in New Hampshire, all the while laughing at the media frenzy he’d created with his lies. Hall seemed nonchalant about his fate—possibly he thought he might escape during his transfer back into federal hands. While Hall may have contemplated freedom, the sheriff and district attorney wanted him out of their jurisdiction without delay. Working secretly with naval officials, they hustled the accomplished liar from his cell the morning of February 10, and Undersheriff Frank Hawley accompanied Hall onto a Central New York train bound for Portsmouth. They expected some pushback from his attorney, Mr. Brickner, since they purposely didn’t notify him. Still, they were far too anxious to rid themselves of James Hall to believe anything serious would actually happen. Brickner kicked up a bit of a fuss the next day, citing a lack of respect, but he seemed pleased to see his client gone.

The case had hit another dead end, and Sheriff Gillette had to admit defeat. No other suspects came to light over the years, and the murder of Anna Schumacher remains unsolved. Sadly, her family never saw anyone brought to justice for the loss of a beloved daughter and sister.

Resources:

Democrat & Chronicle

Murder, Mayhem & Madness by Michael T. Keene

Findagrave.com

Ancestry.com

A sad tale. Wondering if any DNA evidence would have survived a century hence. Seems unlikely. The killer and any of his offspring are now long dead.

LikeLike