Part One

If you’re familiar with the drive on NYS Route 39 between Perry and Geneseo, you’ll know about the Boyd-Parker Park just outside of Cuylerville on the south side of the road. It’s a beautiful and peaceful spot along the highway, but in 1779, it was a different story. In fact, the park’s origin is a war story that has been commemorated since the end of the Revolutionary War.

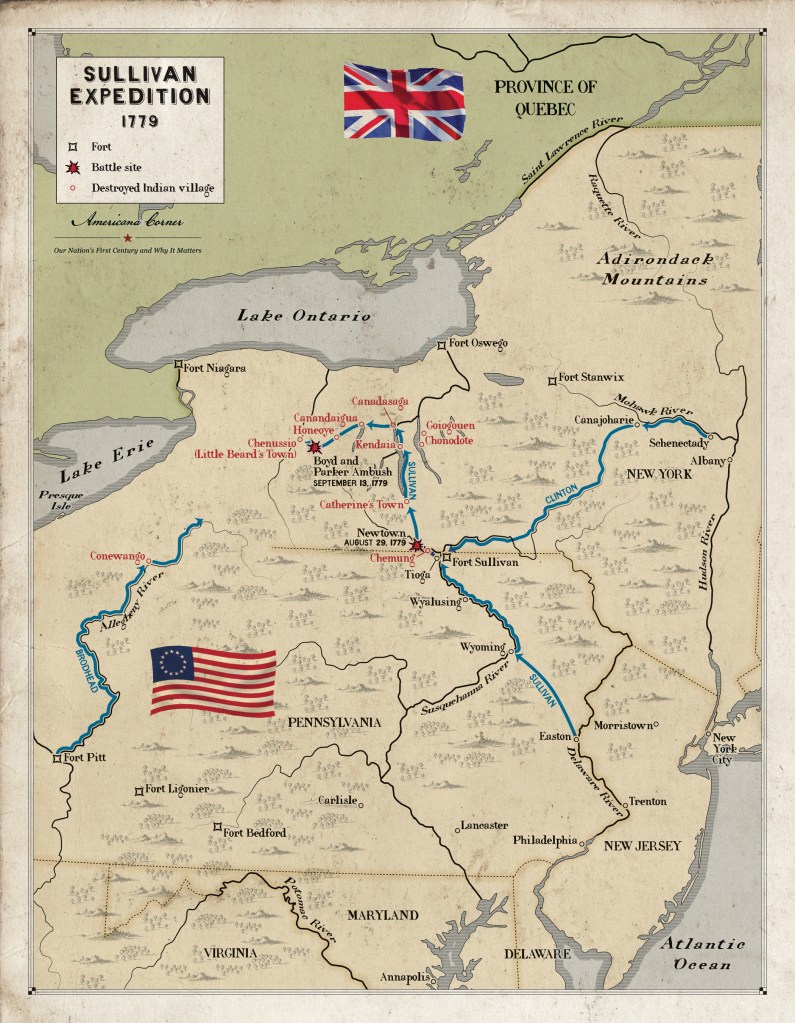

Clinton-Sullivan Campaign, May-October 1779

In May of 1779, General John Sullivan received a letter from the commander of the American Continental Army, General George Washington, to immediately mount a campaign against the Six Nations Confederacy. This mission had been in the wings for at least a year, as New York Governor George Clinton had been lobbying the Continental Congress and General Washington to take action against the Seneca, Onondaga, Mohawk, Cayuga, and Tuscarora nations that were aiding Butler’s Rangers in destroying settler communities from eastern to western New York and northern Pennsylvania. Two particularly heinous events, the Wyoming Massacre in Pennsylvania and the Cherry Creek Massacre in New York, were the final straws as Congress authorized the campaign to destroy the Six Nations Confederacy.

General George Washington sent a letter to General John Sullivan, who was in Easton, Pennsylvania, with these orders: “The expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the six nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.”

General Washington wanted Sullivan and General James Clinton (the brother of Governor George Clinton) to quickly eliminate the Six Nations’ threat in the frontier regions of New York. Four brigades of Continental troops were committed to the campaign, which was roughly 25 percent of the entire army, about 4,500 men. However, the terrain and the construction of roads to reach the meeting place agreed upon in Tioga, New York, slowed General Sullivan’s troops for weeks. General Clinton’s forces were at Otsego Lake, building a dam to raise the level of the Susquehanna River so they could travel south to meet Sullivan. The entire mission was terribly behind schedule, and General Washington grew more impatient with the lack of results from Sullivan.

By late August 1779, Sullivan’s men had finally reached Tioga, and their first victory was the destruction of Chemung, a community inhabited by both settlers and Indians. Loyalist Lt. Colonel John Butler realized he was significantly outnumbered and attempted to convince the chiefs that guerrilla warfare was the most effective approach. He wanted to use small parties of his Rangers and Indians to badger and delay the army rather than face them on the battlefield. The chiefs would not agree, and when they met Sullivan and Clinton’s forces at Newtown, New York (near present-day Elmira), it was disastrous for Butler and the Six Nations. Sullivan’s men quickly discerned the trap laid for them and soundly defeated the enemy.

With this win, the Americans felt assured of victory. General Sullivan ordered the men to travel light on half rations as they hurried toward the Finger Lakes region with the ultimate goal of reaching the Genesee River. This was an arduous march with cattle and supplies being lost along the way.

Major James Norris’ diary recorded this on the 30th of August 1779: “The Army Remaind on the Ground to day & Destroyd a vast Quantity of Corn and about 40 Houses—The Army by a Request of General Sullivan Agreed to live on half a Pound of Beef and half a Pound of flower Pr Day, for the future as long as it might found Necessary our Provisions being short—This night the sick and Wounded together with the Ammunition Waggons, and four of our Heavyest Pieces of Artilery, are sent back to Tiago by water, which will Enable the Army to proceed with much Greater ease and Rapidity…”

The army continued its march through the wilderness of the New York frontier, destroying Indian villages of considerable size and decimating fields of corn, squash, cucumbers, and other vegetables. These houses were not the bark longhouses of decades before, but were frame houses with orderly streets laid out in these prosperous towns. Due to the half-rations situation, the men foraged in these fields before setting fire to them to supplement their meager food supplies. Despite the campaign’s slow progress, Sullivan’s army arrived at harvest time, which allowed them to both profit from the bounty of gardens and orchards and also decimate the Indians’ food supply before winter. By September 1st, the army arrived at Seneca Lake, leaving a path of total destruction in their wake.

Another entry from Major Norris’ diary entry for the 2nd of September, 1779: “The Army laying Still to day to Recrute and Destroy the town Corn & a Very old Squaw was found in the Bushes to day who was not able to go off with the rest, who Informs us that Butler with the Torys went from this Place with all the Boats the day before yesterday, the Indian Warriers Moved off their families and Effects, yesterday Morning, and then Returned and stay’d till sun sett, she says the Squaws and young Indians were very loth to leve the town, but were for giving Themselves up, but the warriers would not agree to it…” The exodus of the Indians from their villages to British Fort Niagara had begun.

Lt. Colonel Butler was desperate to turn the advantage away from the Americans and take control of the region by rallying the Senecas to defend his base of operations at Kanadesaga, a major Seneca town. The humiliating defeat at Newtown still overshadowed the Senecas, and they were focused on getting their families to the safety of Fort Niagara. Sullivan continued unimpeded and was able to raze town after town around Canandaigua Lake by September 9th. It was then that General Sullivan began to look further west toward the Genesee Valley, knowing that Little Beard’s Town was a stronghold of the Senecas located on the west side of the Genesee River in present-day Cuylerville. Little Beard’s Town was also known as Genesee Castle or Chenussio.

Thomas Boyd

Lieutenant Thomas Boyd was selected by General Sullivan to lead a scouting party to the west to plan his strategy to take Chenussio. Boyd was a seasoned soldier and had served under Benedict Arnold in 1775 and was present when General Burgoyne surrendered to American forces in October 1778.

He was born in Washingtonville, Pennsylvania, in 1757, and was described as a man of average height, “strongly built, fine looking, sociable and agreeable in all his manners,” by W. P. Boyd at a Boyd Clan Meeting in 1889. Boyd also fought in the Battle of Wyoming, and in May of 1779, he was serving in Michael Simpson’s rifle company in Schoharie, New York.

During his time in Schoharie, he’d been courting a young woman named Cornelia Becker, whose father was of some importance in the town. The relationship grew serious, and matrimony seemed imminent. However, there was a terrible public scene between Cornelia and Thomas as he prepared to leave with his company to join General Clinton’s forces at Otsego Lake in May 1779. Cornelia belatedly learned that her beau and supposed fiancé was leaving town without marrying her. Rushing to the camp, the tearful Cornelia pleaded with the young lieutenant to marry her before he left, as she was pregnant. Thomas Boyd put her off with promises to return once his mission was completed. Cornelia was quite finished with Boyd’s empty promises and is reported to have said, if he went off without marrying her, she hoped and prayed that he would be tortured and cut up by the savages. While the drama played out, Boyd’s commanding officer came upon the pair, reprimanding Boyd for holding up the movement of troops. Embarrassed in front of his men and the colonel, Boyd drew his sword and, pointing the blade at Cornelia’s bosom, threatened to stab her if she didn’t leave him immediately. After this miserable parting, Cornelia never saw Thomas Boyd again and gave birth to a daughter, Catherine, in the fall of 1779.

Cornelia Becker was likely far from Lieutenant Thomas Boyd’s thoughts as he selected a large scouting party with his sergeant, Michael Parker. His confidence was high that they would successfully gather the information General Sullivan needed to advance the troops and complete the mission. The Genesee Valley was beautiful with grass higher than their heads, the rich farming land evident in the lush vegetable gardens and fields of tall corn. Their Oneida scout, Hanyost Thaosagwat knew the area, and because the troops had met with minimal resistance for weeks since Newtown, the scouting mission would be simple.

Resources:

The Life and Parentage of Lieut. Thomas Boyd, W. P. Boyd, 1889

General John Sullivan’s Indian Expedition 1779, Journals of Officers

The Clinton-Sullivan Campaign of 1779, National Park Service