Early in the 19th century, as villages dotted the landscape along the Genesee River and Western New York, churches sprang up, and residents organized according to Protestant doctrinal persuasions—Presbyterian, Baptist, Congregational, and Methodist-Episcopal. The preachers regularly came along, but musicians were scarce, as were musical instruments and printed music. This unsurprisingly led to dismal singing in the small congregations. Some congregants may have had an old family hymnal, but words were merely printed in them and were without musical notation. For that, a separate tune book was needed, and the tunes had names such as Regent Square, Lancashire, St. Dunstain, Winchester, and many more. Selecting the correct tune to go with a hymn for meter was the next challenge and not many had the skills to put the lyrics with the appropriate tune. Some churches had a proficient singer who sang a line from a hymn, which was echoed by the congregation throughout the hymn. This method of antiphonal singing was called “lining,” and eventually, the tune and the words were learned by rote. However, there was a great desire to improve church singing in worship and educate the general population in the rudiments of music. Traveling singing masters came upon the scene and often organized singing schools in a village for a few weeks or months, culminating their work with a concert before going on to a new area.

In 1817, a group in Warsaw, New York, organized a music society for the “encouragement of vocal and instrumental church music.” As the years went by, singing schools and/or musical societies became the norm during the long winter months when life slowed on the farms, and people looked for social occasions and improving their education. Making music solved this problem nicely, with young men and women enjoying a relatively unchaperoned situation in sleigh rides to and from the classes. However, singers of all ages were usually invited to attend singing schools held at churches or public halls. These were highly organized societies with officers, fees, and a constitution.

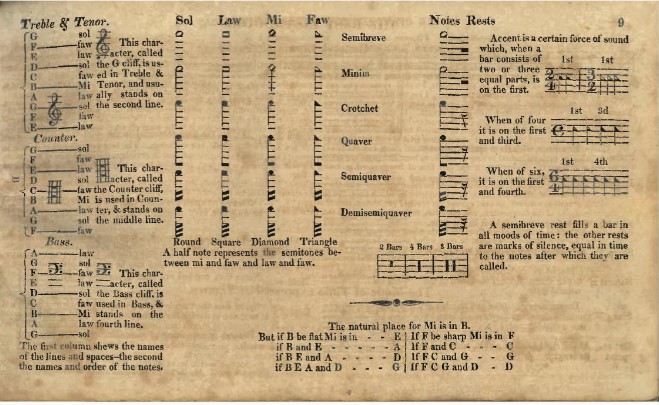

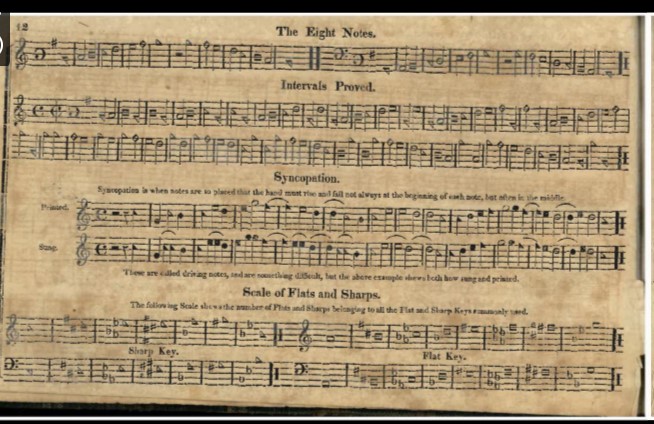

Instructors began with basic music theory, which included scales, reading notes, time signatures, and learning the language of musical notation that governs volume, repeated lines, tempo, and expression. Many teachers used Smith & Little’s “Easy Instructor” tune book that was divided into lessons on music theory and learning to sing in unison, then in parts. Members from different churches practiced together, and friendly competition between church choirs was inevitable as the group became more skilled. As usual, there were some divas, and early Warsaw historian Professor D. D. Snyder recounts an evening when Sears Belden of Pavilion, who taught a school in 1835-36, had trouble with some “highly strung” singers who refused to sing for some reason. He nipped the problem in the bud by selecting the hymn, “Let Those Refuse to Sing Who Never Knew Their God.” With this dire warning, all the singers pulled themselves together and sang.

Eventually, “parlor songs” or secular songs were added to singing schools’ repertoires, and glee clubs came into being from this music. Instrumentalists weren’t left out of training, and in 1840, Warsaw Baptist Church singers organized a new association, which cost members $1.00 and their signature on the society’s constitution. Nearly 100 people came to learn how to sing and play musical instruments. A nineteen-year-old, David Snyder, was hired to teach the chorus, and there was an orchestra section of trombones, violins, double bass viol, and a big bass horn called the ophicleide, which was a French instrument in the bugle family about eight feet long, and a forerunner of the tuba. This school was a rousing success, but in the winter of 1840, there were many such schools around the area—Hall’s Corners, Johnsonburg, North Java, Castile, Portage, Perry, Avon, Scottsville, and many more.

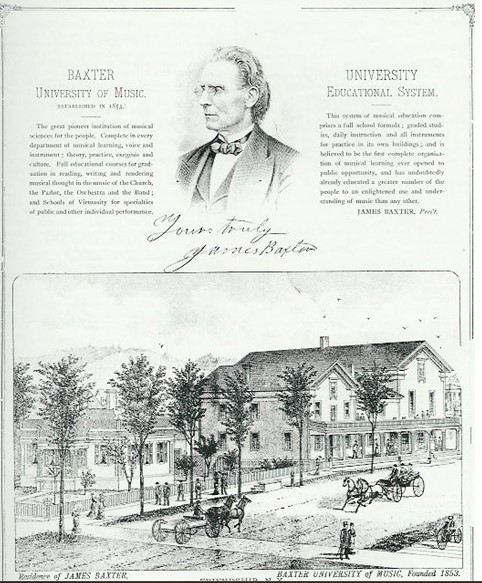

Further south along the Genesee, James Baxter of Friendship started his own school, which was opened in 1853 as the Baxter Music Room. He was an accomplished musician who didn’t fit into the career track of farming for most young men of the time. His continued success led to larger quarters in the village, and it was renamed Baxter University of Music in 1870. The university offered three levels of degrees in church, parlor, orchestral, and band music. At the height of its popularity, the school was said to have 150 pupils from 16 states, three territories, and Canada. Many graduates went on to teach music in schools and privately while also performing in bands and orchestras. Baxter also published his own music books through publishing houses in New York City, Boston, and Chicago.

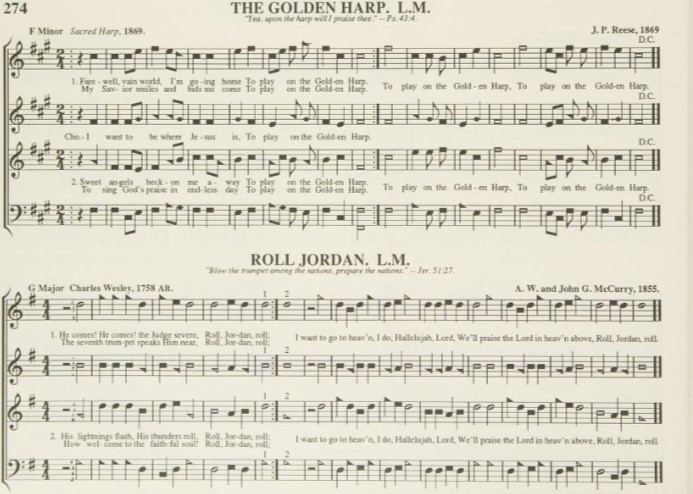

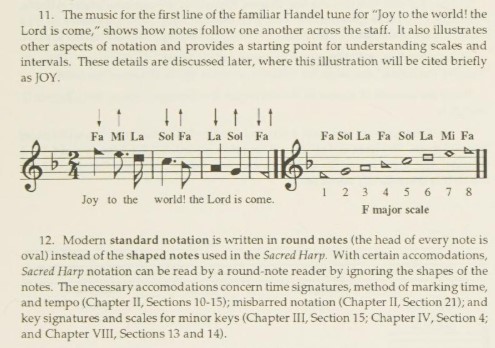

By the time of the Civil War, there were many printed tune books that were part of the fabric of American music education, which local churches and not schools largely managed. The tune book Sacred Harp was primarily used in the South, and it relied on a shape-note system to teach pitch and sight reading. Sacred Harp singing is still popular today, which is acapella (without instruments) and performed in a circle. It is an authentic American style of sacred singing, mainly used in Primitive Baptist and Mennonite churches. YouTube has many examples, and it is worth watching this unique method.

Sometime during the Civil War, Warsaw was visited by the famous hymn writer and music teacher Philip P. Bliss, who was connected with the famous evangelist Dwight L. Moody and his revival services. He reportedly spent a year in the village teaching singing schools and leading the Congregational Church choir. Bliss wrote many familiar hymns still sung in churches today, such as Hallelujah! What a Savior!, Wonderful Words of Life, and Let the Lower Lights be Burning. He also wrote the music for Horatio Spafford’s hymn It is Well with My Soul. Sadly, Bliss and his wife were both killed in a tragic train accident in 1876. He was only 38 years old.

At the turn of the century and with the rise of public education, singing schools largely disappeared in the first decade, and church music education declined. Today, sadly, singing in parts is a lost art in many churches and secular settings. Some of this can be blamed on budget cuts to music and art in schools, but also to a lack of interest in churches, which have turned to worship bands rather than choirs. As someone who has been in choirs since middle school, there is something wonderful about singing in a choir either acapella or with instruments. Oxford University’s study on the health benefits of singing in a choir included less stress, improved breathing and posture, social connections, aids mental health, endorphins release during singing, giving singers a sense of well-being, and the satisfaction of working together to create beautiful music. Perhaps it’s time to revive the tune book and singing schools.

Resources:

Historical Wyoming, Warsaw’s Early Singing Schools, Jan. 1959

Allegany County Historical Society, James Baxter bio, Baxter University of Music

Internet Archive: Sacred Harp, American Tune Book, Easy Instructor

Hymnary. Org – P. P. Bliss bio

Democrat & Chronicle – various articles