For history researchers, personal letters and diaries can be treasure troves of information, not only about the person you’re researching but also about the time period in which they lived. I recently ran across one of those letters—a time capsule chockfull of cultural and historical insights from 1905.

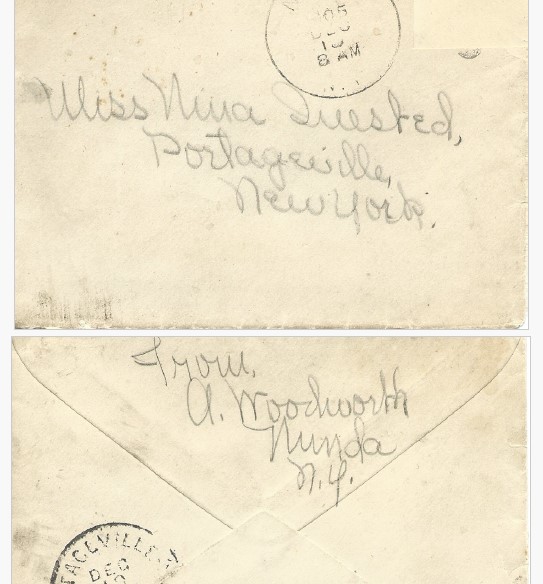

The letter was written to my husband’s paternal grandmother, Nina Quested, who was 17 years old in 1905 and lived in Portageville, New York. The sender was a friend, aged 16, who lived in Nunda, New York, just over the Genesee River and about six miles from her home. The transcribed letter follows:

Nunda, N.Y.

Dec.’ -05

Sat. Evening

Dear Nina,

Your very welcome letter was received some time ago. I was very glad to get it. You always tell all the news. (Just as if there was much to tell of Portageville. Haha!) Yes, I have come to the conclusion that Portageville is rather a slow old place.

Over here everyone dances and skates, etc. At Portage, they don’t. They haven’t even got the postal fad. Everyone spends their spare “dough” for postals here. There are three or four places in town where we can buy them. I entended [sic] to have my pictures taken and placed on postals to send out for Christmas but the man couldn’t get them done.

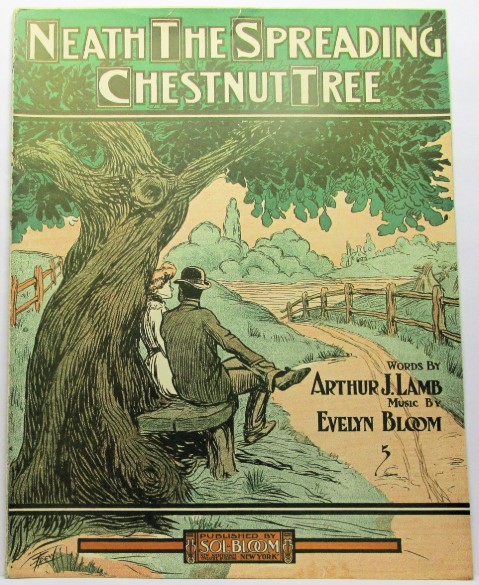

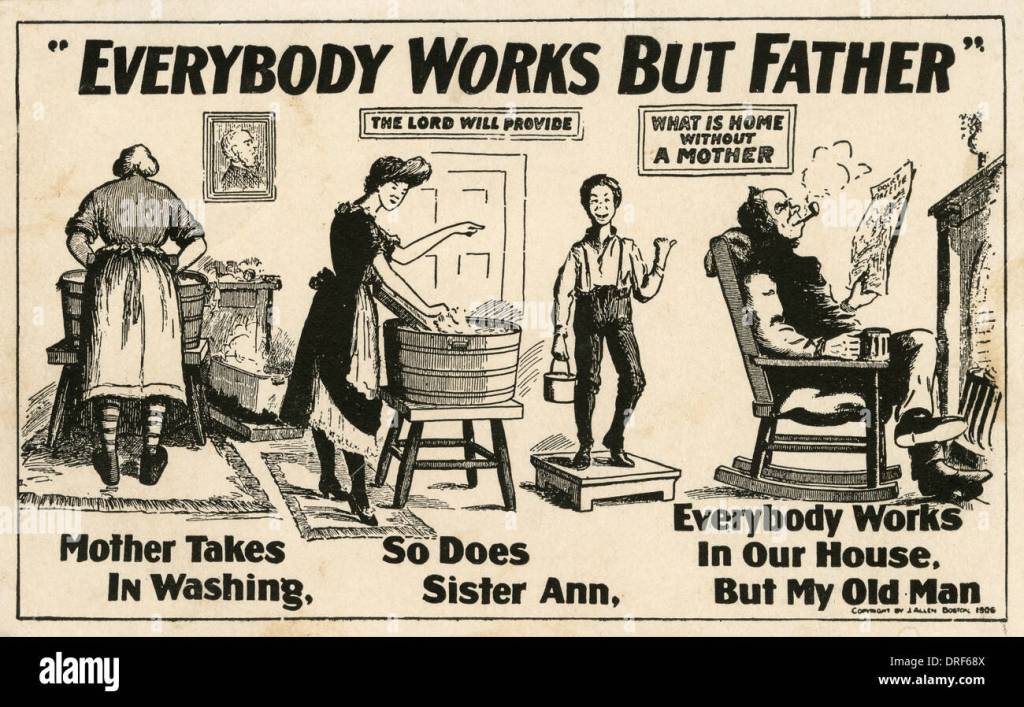

My mother and father have been on a business trip up to Olean, Bradford, Salamanca, etc. and I have kept house. The boys say that they think I have a snap because I don’t have to do so very much work. I can stay out of school and I get a dollar for doing it, but my snap has ended for my parents came home tonight. They got some music for me at Olean. They got “Moonlight” of course you have heard of it. It is quite old. I got three from New York a few days ago. “Neath the Spreading Chestnut Tree”,” Have You Seen My Henry Brown,” and “Silver Heels.” It seems that Silver Heels is the latest in New York. It is the latest thing everywhere. Anyhow, I got two new songs in Rochester before they got stale. They are, “Everybody Works but Father” and “My Irish Molly O”. The last one is a peach. We hear the very latest things here because Prof. Frank Logan plays everything when it first comes out. One of the cute ones is Rufus Rastus Johnson Brown, What ya gonna do when the rent comes ’round”. There is too much music in the air so will chop it out. There is no news anyhow. The skating is splendid. –A. W.

(P.S). I had a small card party Mon. night in honor of a Mt. Morris girl.

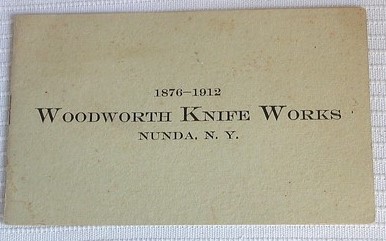

In a little over 300 words, there are many insights into this teenager’s life and popular culture. The letter’s tone and content are certainly that of a teenage girl, even though she’s from another century. Her interests are easy to spot—music, parties, postals, and skating. She’s pretty sure her town is much better than Nina’s, and she’s very current with what’s popular. However, she signed only her initials, but fortunately, the letter was still in the envelope with the return address “A. Woodworth, Nunda, N.Y.” Her identity began as a mystery, but the federal and state censuses soon cleared it up. A. W. was Amy Woodworth, the eldest daughter of Fred and Cora Woodworth of Mill Street, Nunda. Amy’s father owned the Woodworth Knife Works, one of Nunda’s most successful businesses. The brothers she mentions were Clayton and Frederick, both much younger, around five and six years old at the time. She also had a sister, Minnie, who was thirteen. Newspaper records place Nina in Nunda for school at various times, so likely, the two girls struck up a friendship because of that. Here’s more about the Knife Works.

Want to know what slang teens were using in the early 1900s? Amy’s letter helps us out. Dough = money, postals = postcards, peach = really good/nice, snap = easy. What was the postal fad? Postcard correspondence became fashionable from 1905 until World War I in 1918, especially for girls and women in rural communities. It was during the time when telephones weren’t ordinary, and the mail was delivered twice a day. (How things have changed!) The fad helped photographers find a new source of income by having their photographs of scenic places, buildings, and people printed on postcards. Printers designed valentines, birthday cards, and all sorts of other “postals” for feminine correspondence.

Amy spent most of her letter talking about the music of the day, which was something new. She brags about owning all the latest music and seems very knowledgeable. But how was she listening to the music? There was no electricity, smartphone, stereo, or CD player. Her only option was the hand-cranked phonograph, invented by Thomas Edison in the 1870s and available to the public since 1888. Around the time of this letter, a phonograph cost about $20 for a higher-end model and $7 for a basic one. The earliest recordings were on cylinders coated with beeswax, but in 1905, a phonograph that played discs became available. Cylinders only played two minutes of music in the beginning until longer playing ones were developed and were priced from $4 to 50 cents. We can’t be sure if Amy had the latest model or an older one that used cylinders, but the machine would be hand-cranked in either case. She wrote about seven popular songs in 1905, including Neath the Spreading Chestnut Tree by Irving Gillette. Here’s a link to a 1906 cylinder recording of Henry Burr singing this ballad. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VBiFD3zdeGQ.

Ragtime music was popular in the U.S., and Amy seemed to love it, as most of the titles were in that genre. Have You Seen My Henry Brown was recorded in 1905. Here’s the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V-Dwy6SFGWg. Harry Von Tilzer’s ragtime hit in 1905, Rufus Rastus Johnson Brown, is a classic, and here’s a ragtime band performing this humorous song: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z-PpSoDaYao.

Ragtime music had been around since the 1890s, and its syncopated style, with banjo and piano as the main instruments, is a uniquely American music style that gave way to jazz in the 1920s. Scott Joplin and Jelly Roll Morton were the big names in ragtime, and Joplin’s music was featured in the 1973 film The Sting, which starred Robert Redford and Paul Newman.

Amy’s letter mentions Prof. Frank Logan, which immediately brought a teacher to mind, but after some research, my husband found that he was a seventeen-year-old who lived with his grandparents in Nunda in 1905. For some reason, he earned the nickname Prof. With a bit more detective work, we found that Frank Logan was an excellent pianist and most likely had the sheet music for all the latest hits. He left Nunda after high school to become a professional musician based in Michigan. He eventually had his own band, which entertained radio audiences later on, and he lived a rather colorful life. The radio wouldn’t become a part of American home technology until the 1920s.

The other thing Amy writes about is travel. Her parents were on a business trip that included several cities in the Southern Tier, her own travel to Rochester, and possibly New York City. Automobiles were not the primary mode of transportation in 1905, but the train certainly was for longer trips, while horse and buggy was used for local travel. Daily trains were available right in Nunda and it was a “snap” to purchase tickets at the depot.

As for the mention of a card party, the card games popular in the early 1900s were Rummy, Canasta, Hearts, and Whist. The girls may have also played Pig or Donkey, which were also favorites.

Amy’s letter gives us a glimpse into the turn-of-the-century life in a small town and shows that teenage girls haven’t changed much over the centuries. She married in 1916 and had two children with her husband, Smith Higgins, a tailor from Warsaw. Amy was always active in the Methodist Church and the community until after her husband’s death in 1947, when she moved away.

An interesting tidbit in the Nunda News was that on December 30, 1952, she appeared on the television show Strike it Rich, a long-running game show as a contestant. The show’s premise was odd, as contestants had to share a story of their need for cash because of illness or some other personal tragedy. They had to answer four questions successfully to win a cash prize. A “heartline” was opened for losers, which was a telephone line for viewers to offer either cash or merchandise to help out the unsuccessful contestant. One can only wonder what led Amy to write a letter to the show. As with any research endeavor, rabbit holes and more questions keep coming.

For readers who may have a stash of old letters, you might find your own treasures in the written word. Who knows what you may find.

Resources:

Amy Woodworth 1905 Letter – Wallace Archives

Nunda Historical Society

Nunda News January 1953

Library of Congress – Ragtime Music and Phonograph History

Wikipedia – Strike it Rich

Federal Census – 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940

New York State Census – 1915, 1925

Findagrave.com

Ancestry records