Part One

When the Genesee River Valley opened for settlement in the early 1800s, it was driven primarily by the Holland Land Company, a group of Dutch investors and banks. Ambitious men of all types poured into the area, planning to make their fortunes when they saw the rich resources along the river. One of these men was Elisha Johnson who would not only be a perennial politician in Rochester but was also responsible for building significant infrastructure for the Genesee Country. For readers who own property in Allegany, Livingston, or Wyoming Counties, a quick perusal of your deed will show Elisha Johnson as the man who subdivided the Cottringer Tract in 1807, a piece of land that straddled the winding Genesee River.

EARLY LIFE

Elisha Johnson was born in the Wells, Vermont area on November 29, 1784, the oldest child of Ebenezer and Deborah Lathrop Johnson. Ebenezer had a colorful background and was a famous privateer during the Revolutionary War before eventually settling in Chautauqua County years later and then in Buffalo, New York.

Elisha graduated from Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, becoming a surveyor and engineer. In 1805, Elisha married Elizabeth Jackson, who was also from Vermont, and their son, Mortimer Fitz Johnson, was born in 1806, then daughter Mary Abigail in 1814. Three more daughters would follow. The family moved west to New York State, becoming part of the throng of pioneers coming from New England and Central New York to the western frontier. The Johnsons made the village of Rochester home in 1817, where Elisha’s ambitions as an engineer were soon realized. He was eager to demonstrate his engineering skills when he came to Western New York.

ROCHESTER LIFE

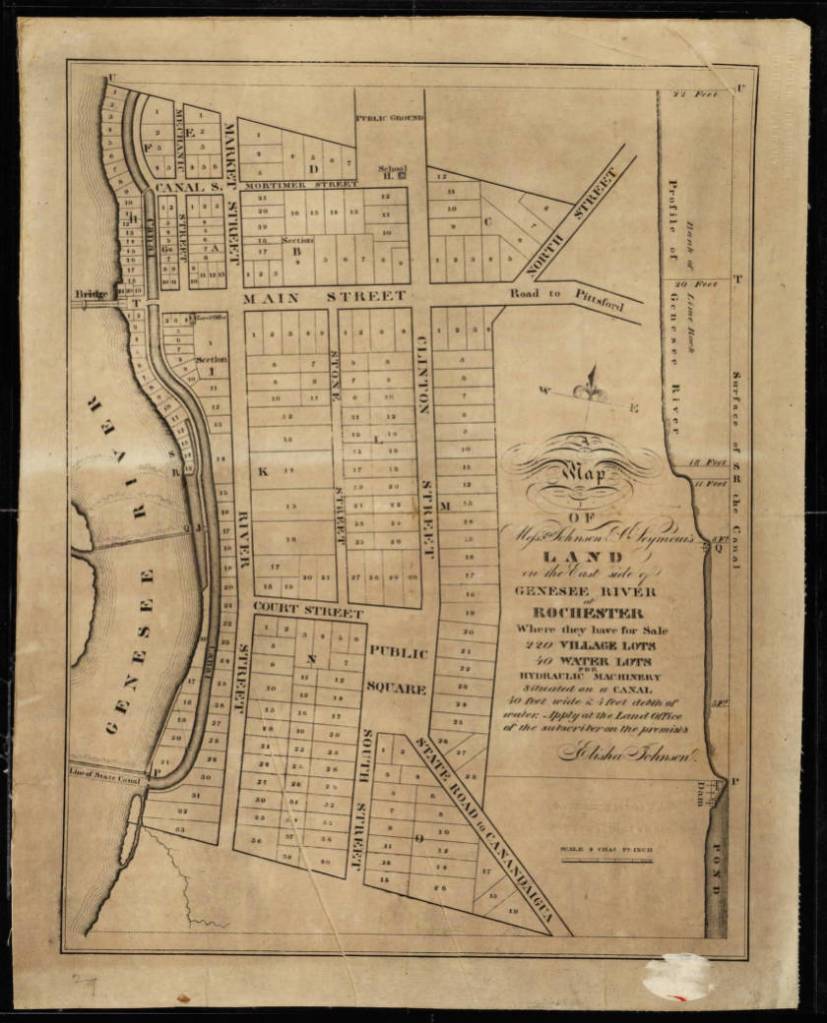

Upon his arrival in the frontier village of Rochester, he immediately negotiated the purchase of 80 acres of land from Enos Stone, a farmer whose farm was in the center of Rochester, and his acreage followed the east side of the Genesee River. The price tag was steep–$10,000 for the prime acreage, and Johnson immediately began the work of surveying to create building lots, selling them to the stream of pioneers headed west. Mills for both timber and flour were always an immediate need for any new village, and he also began the construction of a dam near the present Court Street Bridge. He then proceeded to dig a mill canal from there to Main Street, securing the water power needed by the mills. He partnered with Orson Seymour and several others to provide power to various lumber and flour mills in the growing village. The project’s final cost was $12,000 (almost $300k today), quickly proving profitable for the men. The blasting of the millrace/canal was coordinated with the 4th of July celebration in 1817, which was recorded in the memoirs of Edwin Scranton, an early Rochester resident.

The day was fine and not an accident occurred to mar the general joy. The Rev. Comfort Williams said grace, and then, amid jokes and merriment, the dinner was eaten with great relish. Then came the toasts, which were honored by the firing of ordnance as they were drunk. This ordnance was 20 blasts which had (sic) put down in the race by direction of Mr. Johnson the day before. The first toast was “Our country; prosperity attend it!” Then two of the blasts were touched off, making the woods resound…Then followed other toasts, the blasts doing honor to them until all were ended. The people were wild with joy and every man shook hands with his fellow pioneer…

Joy no doubt was spurred on by the liberal number of toasts (with frontier whisky) that day, but the occasion marked progress and prosperity for Rochester.

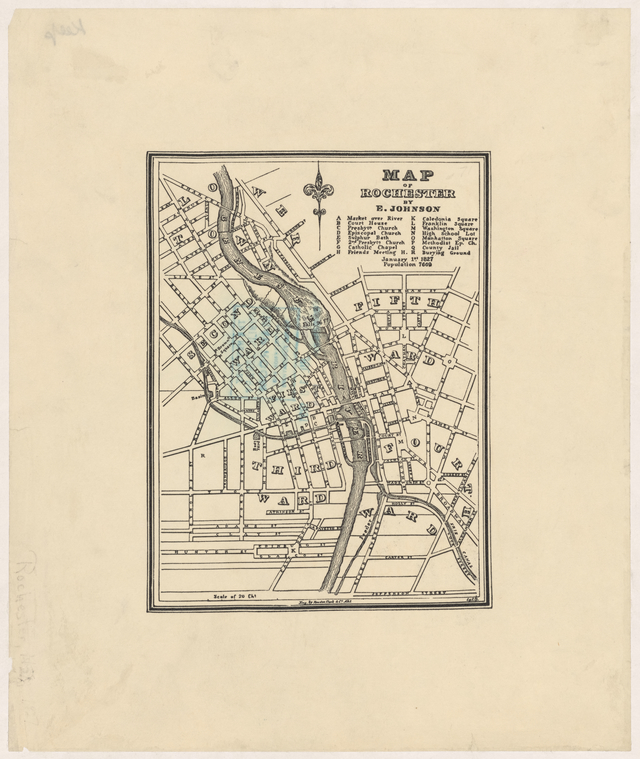

The Johnson family grew between 1816 and 1822 with the arrival of daughters Emily, Julia, and Helen. Not only did his family increase, but business burgeoned with infrastructure projects in and around Rochester, with Elisha designing and constructing the second Main Street Bridge, the first bridge being of inferior construction and in unsafe condition. He also gave the land from the east side of the Genesee to the middle of the river to build an aqueduct in 1821, which would carry the Erie Canal across the Genesee River. Land for the First Methodist Church built on South Avenue was donated by the engineer and he built the family home on South Clinton and Johnson Street, later gifting a portion of it to the city known as Washington Square Park. Johnson surveyed the village of Carthage, which was two miles north of Rochester, and then built a horse railroad to connect the two villages. This 1832 enterprise was for travel convenience, consisting of two passenger cars drawn along a track by a team of horses. Elisha drew the first city maps of Rochester and was heavily involved in village affairs becoming the village president for three terms, and was the city’s mayor in 1838.

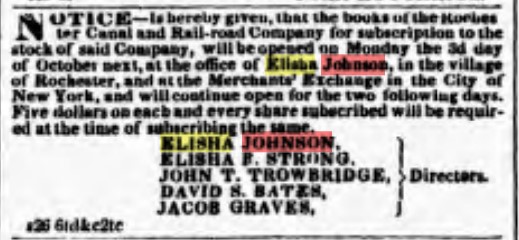

The nascent railroad was where Elisha Johnson would shine. In 1837, he was the chief engineer for the Tonawanda Railroad that ran between Batavia and Rochester. It was a crude, single wooden track, and the primitive steam engine chugged along without a cowcatcher or whistle. The train engineer blew a bugle to announce his presence at crossings in those early days of train travel. His crowning achievement was as the builder of the Great Western Railroad that spanned from Toronto to Niagara Falls, then westward to the Detroit River. It was a massive and vital international project that opened faster options for transporting goods to new markets and passengers. He also received a patent for his unique method of laying railroad tracks in 1835. It seemed that Elisha was at the height of his career, and then a new opportunity came along that changed everything.

GENESEE VALLEY CANAL PROJECT

New York State had vacillated for years over building another canal despite the success of the Erie Canal. The proposed Genesee Valley Canal would follow the river from Olean, New York, to Rochester to connect with the Erie Canal. There were no railroads servicing the route, and this waterway promised easy transport of goods and people along a safer and more reliable environment than the capricious Genesee that flooded in spring and dried up in spots in the summer. (For more about the Genesee Valley Canal) The feted Johnson was determined to be part of the project and, between 1838 and 1839, won the contract to build a section of the canal that would run through what is now Letchworth State Park. Here, Johnson would meet his greatest engineering challenge, tunneling through rock to make way for the canal. He planned a 1,200-foot tunnel to bring the canal out at a point opposite the Glen Iris. The tunnel area was on the opposite side of the river where Inspiration Point is located in the park.

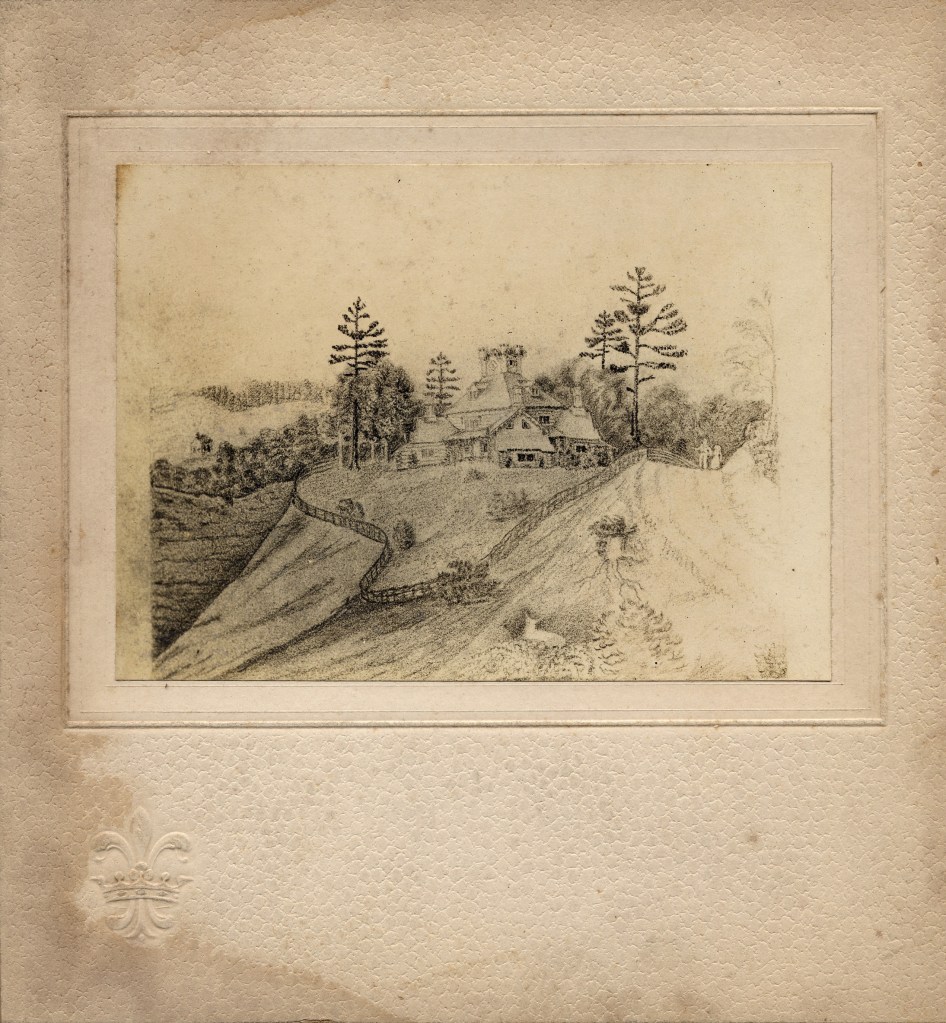

The engineer was taken with the beauty of the river gorge, and anticipating the project would take a long time, he decided to build a home for his family near the project in 1840. That way, he could easily walk to work and wouldn’t be separated from his family for long periods. Inspiration for what would be named Hornby Lodge likely came from the politics of the day—“Tippee Canoe and Tyler Too.” Log cabins, raccoons, and hard cider were all part of the lyrics of a campaign song for the Whigs that year, so Johnson (a Whig) drew up plans for an exceptionally grand log cabin. It was built on an outcropping of rock overlooking the river gorge while the tunnel work progressed underneath the house.

In her book Genesee Echoes, Mildred Anderson described the four-story “cabin” as follows: The main part of the house was square, with each corner cut off and a wing built on. A door from each wing opened into a large room in the center, making it an octagon. In the center of the large room, and used as a support for the timbers of the floor of the upper rooms and the roof, stood a large oak tree. The upper rooms of the main house were left rectangular in shape. All the furniture was made from the limbs of trees selected from the surrounding forests. All manner of natural shapes were used.

Besides the woodsy furniture, Johnson filled the house with stuffed animals—squirrels, a raccoon, and birds. A winding staircase from the main room was fastened to the supporting tree leading to a fourth-level observatory deck. Visitors would later recount the glories of the eccentric woodland cabin with its fantastical furnishings and the views across the river gorge. Hornby Lodge was named after the original owner of the Cottringer Tract, William Hornby. Colonel George Williams was the current owner of the acreage at the time and leased the land to Johnson to build his temporary home. The lease was set to terminate when that section of the canal was completed. The area became known as Tunnel Park, with Hornby Lodge atop the rock formation, 100 feet above the tunnel construction beneath it.

A steady stream of visitors came to enjoy the wilds of the gorge at Hornby Lodge and watch the tunnel’s construction. During the winter of 1840-41, the Johnsons planned the wedding of daughter Mary Abigail to Elihu Mumford at the Lodge. Guests from Rochester and Mt. Morris came to celebrate the nuptials on March 16, 1841, only to be caught in a snowstorm that kept the party of 50 from departing for several days.

Thomas Cole, the premier artist of the Hudson River School, was commissioned by friends of New York Governor William H. Seward to paint the glorious autumn colors of the river gorge and Hornby Lodge as a gift to Seward in 1841. The painting was immense—six by eight feet. The reported commission was $1,000, and in 2013, the value of the spectacular painting was over $20 million. Cole also presented the Johnsons with a pencil sketch of the house at the time; a thank you for their hospitality as he completed the commission for Seward.

While the Johnson family’s social life was a whirl of activity, the tunnel construction encountered serious problems. The ambitious project was in the time of hand digging with the assistance of black powder to clear the rock. But from the start, quicksand and rock slides hampered the progress of the proposed 1,200′ long, 27′ high, and 20′ wide tunnel. Such an undertaking in the challenging terrain was a new venture for the experienced engineer, and he met with constant setbacks. The work continued around the clock, with blasting often occurring at night, which shook the house above. Despite his best efforts, Elisha Johnson had failed. With a state-wide recession that would cause the halt of canal funding, problems with his lease of the Lodge’s site, and an investigation into his questionable billing practices, he and his family left Hornby Lodge in 1844 or 1845. The Buffalo Courier reported in July 1851 that the Portage Tunnel was “perhaps the greatest single piece of folly ever perpetrated in the history of our public works. The sum of $180,000 was expended thereon, and when eventually given up, the construction of the open canal was found to cost less than half the amount which would be required to finish the Tunnel.” However, Elisha Johnson wouldn’t read this article since he had already left New York State years before when an opportunity presented itself south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Part Two – Ambition by Design: The Tellico Mansion and Ironworks

Resources: Genesee Echoes by Mildred Anderson, Letchworthparkhistory.com, Arch Merrill’s articles for the Democrat & Chronicle- 1948,1959, Buffalo Courier July 30, 1851, Western New Yorker, September 11, 1855, Wyoming County Times, September 13, 1894