PART TWO – Moses Van Campen could not finish the final weeks of Sullivan’s Campaign, which ended in October 1779. He was sent home to recover from “camp fever” in September, which was likely typhus, a common illness within military camps because of unsanitary conditions, especially with foul water and food spoilage. His recovery took some time, but by March 1780, his father asked him to accompany him and other family members, who had wintered in Fort Wheeler, to begin rebuilding their homes that the Iroquois had burned. These farmers were also anxious to look over their fields and make plans to plant grain as well. The party consisted of his father, Cornelius, younger brother, Nicholas, plus an uncle and cousin. A neighbor, Peter Pence, was also with them. The men were also setting up camps and equipment to make maple sugar along the creek. The success of the Sullivan Campaign gave the group a sense of safety as they went about their business, hopeful of rebuilding what they’d lost. They had divided into two groups about four miles from the fort and within one-half mile of each other, with only one rifle for each camp.

Unknown to the Van Campens and their neighbors, a large band of Indians was working its way toward them, splitting into three smaller groups to surprise the isolated camps as the men went about collecting sap and boiling it down in kettles. The aroma of boiling sweet sap no doubt helped them locate these camps. On March 27, 1780, Asa Upton and 13-year-old Jonah Rogers were making sugar on the Susquehanna near Shawnee Flats and were surprised by one of these groups. Upton was shot dead and scalped, and the boy was taken prisoner, being told he was going to Fort Niagara. Another band went on to Fishing Creek, where Moses’ uncle, cousin, and Peter Pence were working. The uncle was killed while they took his cousin and Pence as prisoners, commandeering their sole rifle. Continuing their way along the creek, the Indians came upon Moses, Cornelius, and Nicholas on March 29.

A spear was launched from the undergrowth, impaling Cornelius in front of his two sons. While the man was still dying, the warrior scalped him and then slit his throat. Young Nicholas, in shock and terror, cried out, and he was immediately struck in the head with a tomahawk. Moses had been pinioned by two other Indians and made to watch his brother scalped as he died. Then, the man drew his spear from Cornelius’ body and threw it at Moses. Despite being held, Moses was able to jerk away from the projectile so that he only sustained a flesh wound. Now, would they kill him or take him prisoner? Keeping his expression impassive with the knowledge that his life depended on showing no emotion to his captors, Moses was successful and taken prisoner.

Two of Cornelius’ horses were loaded with the Indians’ plunder, the other rifle was taken, and Moses’ hands were tied. He became part of the prisoner entourage that continued their raiding along Fishing Creek that day. They marched on, taking more unsuspecting men who were making sugar as prisoners. One of them was Adam Pike, who had served in the Continental Army. The men trudged on to an appointed meeting place with the two other small bands, but signs of a violent struggle were everywhere, which made Moses nervous. Their future was uncertain, and a Fort Niagara prison was not guaranteed. Knowing the ways of the Iroquois well, he knew that escape was their only chance. He quickly formulated a plan against bad odds—ten Iroquois against three prisoners. The two captive boys with them remained ignorant of their scheme. With reluctance, Pence and Pike agreed to it.

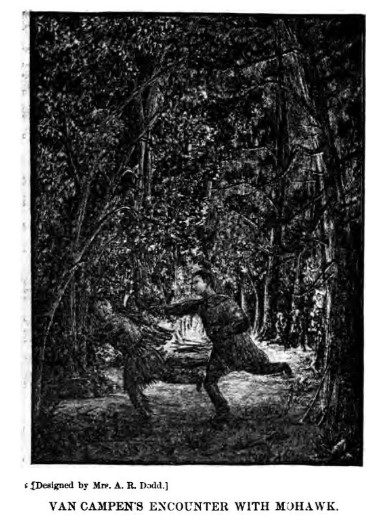

On the night of April 1, a large fire was made in the camp, and the prisoners’ hands were once again bound and directed to their separate sleeping places. Two warriors would flank them later. Van Campen watched one of the captors drop a knife near his feet, and he deftly slid it under his foot. Once all were asleep, he quietly rose, taking the knife to Pence, who cut the ropes. Now freed, Pence took charge of the guns while Pike and Moses snatched up tomahawks. As fate would have it, the two men who guarded Pike awoke, and instead of tomahawking the men as planned, Pike laid back down. Moses struck down both men and turned to dispatch another three. Pence was finally organized and able to shoot four down, and the remaining hostile jumped up, running from the camp with Moses right behind him. A violent struggle ensued with no real victor. The man, whose name was Mohawk, escaped Moses’ grasp and was the only captor to survive. Later in life, Mohawk and Moses would meet on much different terms.

Upon Moses’ return to the camp, he found the quaking Pike on his knees, praying, and Pence yelling at him for being a coward. The two captive young boys had fled into the woods and were nowhere to be seen. The men waited for daylight before moving, gathering guns and supplies. The Rogers boy reappeared at daybreak, and the group made its way back toward Fort Wheeler.

After his successful escape, Moses was commissioned as Ensign of the Company of Rangers for Northumberland County, part of the Continental Army, resuming military life on April 8, 1780. He was then promoted to Lieutenant of the Rangers in February 1781 and tasked with stockading Mrs. James McClure’s home near Fishing Creek. The homestead then became Fort McClure. While he managed the construction of the stockade fence, he met Margaret McClure, his future wife. However, no wedding bells were near for them as he was transferred to Reading, Pennsylvania, by the fall. He was an adjutant to the commander of the Hessian POW camp there, and was in charge of the prisoners between December 1781 and March 1782.

The war continued, and Indian raiding persisted despite Sullivan’s success. Moses and several other soldiers often wore Indian garb and colored their faces to go undercover and observe the movements of the parties in the area. They even infiltrated a camp, killing several combatants and taking back goods that had been plundered from white residents. His daring escape and sterling character was legendary by this time, but his situation was about to change again.

In April 1782, Moses and others were captured by the Senecas at Bald Eagle Creek. The warriors had traveled from Fort Niagara to the Pennsylvania frontier for more raiding. The prisoners received mostly considerate treatment from their captors and were allowed to use knives to cut pieces of meat from an elk the Senecas had killed. They were also allowed to roast it for themselves over the fire. The Senecas tended to one of Moses’ wounded men with herbs and allowed him to watch the treatment given, with Moses encouraging the man to bear the pain and treatment without crying out in order to save his life. The man did recover and was able to continue the march. Moses endured several tests of courage, including successfully walking on a slim log to cross a deep ravine. Any slip would have meant death, but as a skilled woodsman and soldier, he did it easily, earning respect from his captors for the moment. The Seneca warriors kept a close eye on Van Campen, discussing his future by the campfire. One man dressed as a Seneca came over and whispered, “There is only one besides myself in this company that knows anything about you.”

Surprised, Van Campen asked, “And what do you know of me, sir?”

“You are the man who killed the Indians.” It was a reference to his previous capture and escape.

He fully understood that if this man said anything about the incident, he would be tortured and killed without delay. The man was Horatio Jones, another captive who acted as an interpreter for the Senecas. Jones told him he would be safe if he could make it to Fort Niagara without revealing his identity, but until then, it must be kept secret. Jones then warned the men under Van Campen to keep from revealing who their captain was. The march resumed, and the party reached the Genesee River, where they continued until they reached Caneadea. This was a large Seneca town, and the warriors whooped greetings as they neared the log cabins, smoke from the chimneys wafting skyward. The people flocked to congratulate the successful men, look at the prisoners, and loot. They were eager to test the prisoners by forcing them to run a gauntlet of about 165 yards to see what these men were made of.

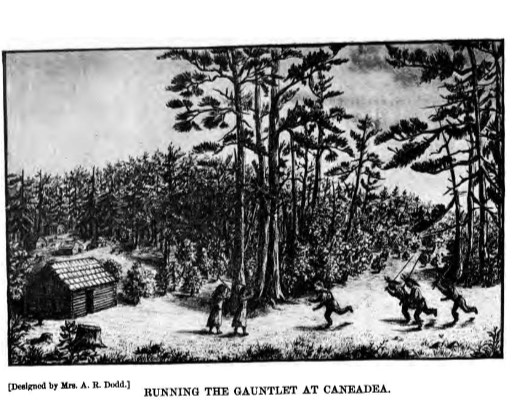

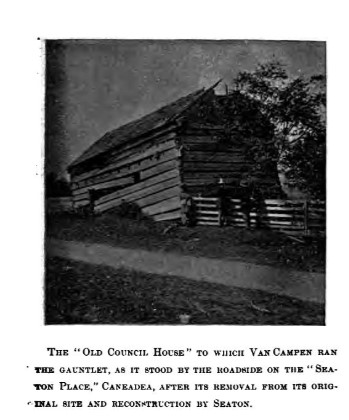

The gauntlet was typically formed by parallel lines of men, women, and children armed with knives, hatchets, sticks, and anything else that would cause injury. If the man could run the distance, he would be safe. If any cowardice or pain was displayed, his life was likely forfeit. But today, it was whips to be used in the gauntlet, and they were to run the distance without being whipped. No parallel lines were formed either, and it was to be a mad dash to the Council House. The warriors waited for the entertainment to begin as women readied the whips. Moses and his men ran, dodging lashes, but he noticed that toward the end of the course, two women were ready with their whips to catch him. Without hesitation, he jumped in the air, hit both of them in the chests with his feet, and they all tumbled to the ground. Moses got up and ran, making the finish line as did his men while the warriors roared in laughter at Van Campen’s quick thinking. He was congratulated and called “shenawana” and “cajena,” meaning brave man and good fellow.

After a few days of rest, the prisoners were again traveling toward Fort Niagara, winding through many Seneca villages, up Buffalo Creek, and finally to Fort Niagara. Relief washed over Moses, who was now in the hands of the British, but a curious ceremony was conducted in which the Senecas had Van Campen adopted by Colonel John Butler, who had lost a son. Explaining the rite to Moses, Butler told him that accommodations would await him in the guardhouse. Moses replied that if he had been adopted into the family, he certainly deserved better lodgings, to which Butler agreed, allowing him to have a comfortable room with a physician. It wasn’t long before the Senecas learned of Van Campen’s identity. Mohawk, the warrior wounded by him in the escape showed up and told the men, showing them the tomahawk scar on the back of his neck. The men immediately turned to Horatio Jones, intensely quizzing him about whether he knew Moses’ name. Jones, elusive as ever, talked his way out of the sticky situation.

However, Moses was charged by the Senecas in the deaths of the party he’d escaped from, and they demanded that he be immediately handed over to them. His life still in danger, Butler offered safety if Moses would come over to the British, promising an officer’s commission. It was strenuously refused, and tensions grew as more warriors gathered at the fort demanding Van Campen. Realizing his future was tenuous, Moses requested honorable conduct by Butler to be held as a British POW and not turned over to the Senecas. Feeling pressure on every side, Butler finally decided to put Van Campen on a vessel to Montreal, ridding himself of his big problem. Moses was held prisoner in a Montreal guardhouse with other Americans until a prisoner exchange was arranged in New York City in November 1782.

He rejoined the Northumberland Rangers in September 1783 and served until November 16, 1783 when he was discharged. The war for independence had been won after seven long, blood-soaked years. The colonies were now the United States of America, and Moses Van Campen’s life would vastly differ as a civilian rather than a scout, spy, and soldier.

PART THREE – MARRIAGE, FAMILY, AND PUBLIC SERVICE

Resources

Sketches of Border Adventures in the Life and Times of Major Moses Van Campen, John S. Minard

Revolutionary War Pension, National Archives

A Narrative of the Capture of Certain Americans at Westmoreland by Savages, Moses Van Campen