One of the Genesee’s most famous and colorful historical figures was Moses Van Campen of Angelica, New York. His long life was filled with incredible exploits and challenges in his younger years, followed by many years of public service in Allegany County as a family man. He was a man “nurtured in the school of rifle and tomahawk.” A Revolutionary War hero and public servant, he remains one of the legendary people of the Genesee country. This is the first of three parts exploring his life.

EARLY LIFE

Moses was the eldest child of Cornelius and Wyntje Depew Van Campen, born in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, on January 21, 1757. Cornelius was of Dutch descent, his wife Wyntje was of French Protestant lineage, and the couple established their home on strong religious beliefs. The same year of Moses’ birth, Cornelius purchased land on the Delaware River in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. This is where Moses and his siblings grew up, becoming a prosperous family in the area.

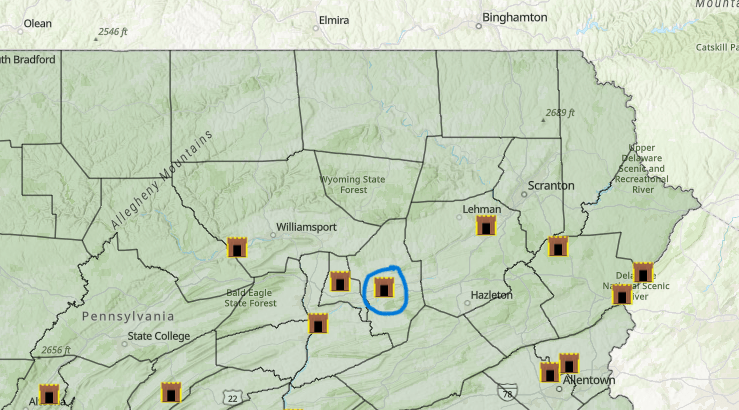

After his mother’s schooling at home, Moses entered public school around age nine, and his focus turned to surveying and navigation as he grew older. In 1769, Cornelius purchased farmland on the Susquehanna River in the Wyoming Valley. He took Moses with him in the spring of 1769 to look over the acreage and establish plans to cultivate it. Although land in the Wyoming Valley was beautiful, with perfect soil for farming, Pennsylvania and Connecticut had been in dispute over the area since 1753. Both Pennsylvania and Connecticut had royal grants from two different English kings for the same land, which led to a real estate conflict between Pennsylvanians and the Susquehanna Company in Connecticut. Tensions were high, and it was quickly apparent to Cornelius that the Wyoming Valley wasn’t a safe place to raise his family. Violent clashes came later and were named the Pennamite-Yankee conflicts. Because of the Wyoming Valley turmoil, the Van Campen family stayed put on their Delaware River homestead until 1773, when Cornelius purchased land along Fishing Creek, about eight miles from the north branch of the Susquehanna River.

EARLY WAR YEARS

Rumors of war were circulating on two different fronts when 1775 began. The birth pangs of the United States had come to the forefront, but Connecticut and Pennsylvania seemed more interested in a civil war over the Wyoming Valley. The valley was located in northeastern Pennsylvania and is in the Wilkes-Barre and Scranton area, which later in the 19th century would be known for its rich coal deposits. Now eighteen, Moses was made captain over a small group of young men that year, and they began practicing military skills as the anticipated war with England became more of a reality. He was already a skilled hunter and had established a good rapport with the local tribes, including the Seneca. They often hunted together and camped in the woods, which, along with his farming life, made him fit and ready to take on any challenge. He was eager to prove his mettle with the enemy.

In December 1775, he enlisted in a militia under the command of Colonel William Plunket to fight the Yankees over the Wyoming Valley. Since his father still owned land there, the owners were expected to participate in any fight for their land. However, Moses asked to take his father’s place and fought in the Battle at Rampart Rocks in the second of the Pennamite-Yankee conflicts near his father’s property. An icy river and a fortified rampart sent Plunket’s band into a retreat, and after some consideration, the men left the area. They had greatly underestimated the organization and fortifications of the Yankees. That year, his father sold the Wyoming Valley property, ending his obligation for future battles. Congress eventually settled the dispute, and Pennsylvania finally gained control over the entire area in 1782.

In 1776, Moses enlisted in Northumberland Company under Colonel Cook of the Continental Army, which was under General George Washington’s command. He was ready to take on the British, full of zeal to gain freedom from the oppressive taxes and rule of the king and Parliament. Instead of marching off from the farm, he was persuaded to give up his commission and stay home to protect his community. The great fear was that the Iroquois Confederacy would agree to fight with the British, which did occur in 1777. Four of the six tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy—Seneca, Mohawk, Onondaga, and Cayuga would join forces with the British army. Their campaign against the colonists was horrific, with women and children killed and tortured along with the men. Houses were burned, gardens and fields destroyed, and livestock slaughtered or scattered. Fear of indiscriminate killing or torture made the residents seek protection in primitive forts along the Susquehanna. Moses was at Reid’s Fort (near Lock Haven, PA) as an Orderly Sergeant, where militia scouts constantly monitored the movements of the Indians in the area. Van Campen’s part was to act on the intelligence to rout the Indians before they could attack again.

Food became scarce this year as crops were abandoned and livestock was lost. Many times, soldiers had no food supplies, and finding an abandoned potato patch was lifesaving. Survival that winter was incredibly hard with severe food shortages coupled with the dangers of daily war against civilians and soldiers.

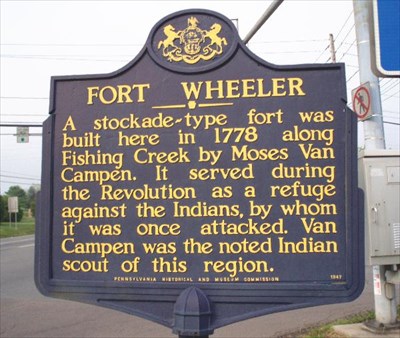

In early 1778, 21-year-old Moses was appointed as a lieutenant over twenty men who had enlisted for a six-month term. They were tasked with building a fort on the banks of Fishing Creek to protect the farms in the area. The fort was outside of present-day Bloomsburg and situated in a heavily populated Native American area. It was constructed on Isaiah Wheeler’s farmland and consequently named Fort Wheeler. The fort was a log structure surrounded by a stockade fence, most likely a typical blockhouse style. Many of the other forts built at that time were stockade fences around a residence. Fort Wheeler was large enough for the families in the area to shelter in as attacks made it impossible for them to live safely in their homes. The fort was attacked twice by Indians within a month of each other, but the small band inside was able to come through unscathed. His account of the May and June attacks in 1778 was part of his application for a Revolutionary War pension in 1838.

FORT WHEELER BATTLES

In the May battle, scouts spied a large party of Indians making its way toward Fishing Creek, and residents fled for their lives to the protection of the fort. They left everything behind, and the hostiles burned farms to the ground after plundering the desirable goods from houses and barns. Both soldiers and Native Americans fought fiercely as the fort came under attack. As darkness fell, the Indians abandoned the fight, removing their dead and injured. However, they continued the burning of homesteads as they left the area. The displaced families gathered their remaining milk cows and anything missed in the fires, taking them to the fort. A cattle yard near the fort was secured where the cows could graze and be milked. In June, sentries spotted movement in the brush as men were milking, and Moses called for ten sharpshooters when he confirmed that the movement was, as suspected, a group of Indians. He and his men quickly slipped from the fort to position themselves between the party and the milkers. The soldiers then stealthily ascended to a ridge and found themselves within pistol range of the attackers. Moses took the first shot and killed the leader. Although his men commenced firing, they didn’t hit their targets, but the Indians fled, as did the men milking the startled cows, dropping milk pails as they ran to the fort.

It was during this dangerous time he became interested in Isaiah Wheeler’s daughter, who was in residence at Fort Wheeler. But, he lost her to another officer and Indian scout who wasn’t hesitant to make his intentions known to the young woman. Moses had little time to lament his romantic loss when he was ordered to track down three Tories (Tories a/k/a Loyalists were American colonists who remained loyal to England and the king.)in the area, who were plundering and burning farms. The young lieutenant took five men with him to hunt down the trio who had been sighted deep in the woods. The small band traveled all night, coming upon a log shanty near dawn. Unfortunately, they were spotted by an early riser before they could surprise the men. Undaunted, Van Campen and his men approached the door, ordering them to surrender. The Tories refused, threatening to blow the head off the first one who came through the door. Even this was no deterrent, and Moses ordered his men to use a hefty oak rail found near the cabin to smash the door down. His plan was to enter the dwelling once there was a big enough opening in the doorway and capture the traitors. The young men were quick to bash in the door, and Van Campen dashed in only to find three rifles trained at his head. Thrusting aside the closest muzzle aimed at his face, the gun went off, black powder bloodying one side of his face and singeing off the hair around his ear. The gunpowder was so embedded in his face that the grains of black powder were visible even in his last years of life. Moses grabbed the culprit and threw him on the floor while his companions quickly subdued the other two. The three men then had their hands bound and were marched to the county authorities and imprisoned.

BUTLER’S RANGERS AND THE BATTLE OF WYOMING

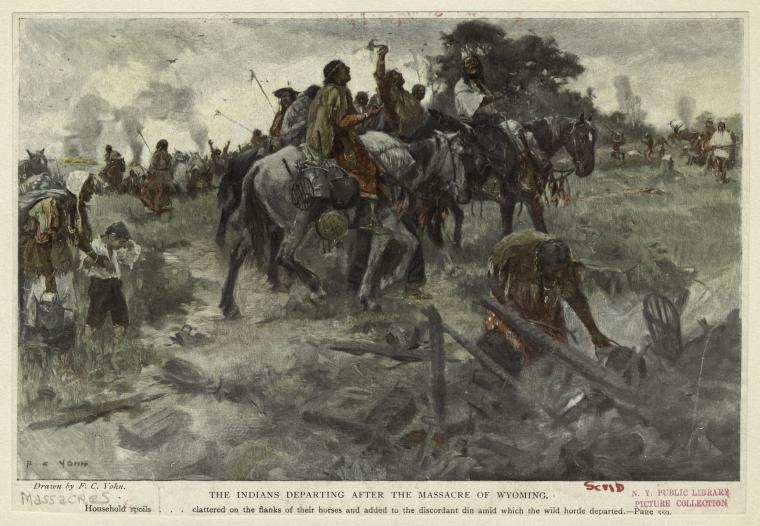

In July, hostilities increased with Butler’s Rangers attacking the settlements in the Wyoming Valley. Moses and his men went to join the fight, not aware of how terribly outnumbered the patriots were. Because of the significant loss of American lives and scalping of the dead, the Battle of Wyoming was known as the Wyoming Massacre.

Major John Butler, a Loyalist who had fled from the Mohawk Valley in New York to Quebec, had organized Butler’s Rangers in 1777. The group, comprised of other displaced Loyalists, partnered with several Iroquois chiefs, mainly Mohawk chief Joseph Brant. The Loyalists and their indigenous allies engaged in a vicious frontier war after the defeat of British General Burgoyne in 1777, who lost control of the Hudson River Valley. In July 1778, Butler sent around 110 of his rangers, along with almost 500 Senecas led by Chief Cornplanter and Chief Sayenqueraghta (Disappearing Smoke), from New York to the much-disputed Wyoming Valley. The Continental Army suffered extraordinary losses, a reported 300 patriots were killed during the short battle over the Wyoming Valley, with the Loyalists and Senecas only reporting a handful of injuries and casualties. The American forces likely numbered less than 400 at the outset of the battle, and Lieutenant Van Campen, somehow survived.

Butler continued his campaigns against the small communities throughout New York and Pennsylvania. The savagery against civilians reached new heights, mainly because Butler’s Rangers attacked the fort and small town of Cherry Valley in central New York on November 11, 1778. It became known as the Cherry Valley Massacre and was led by Chief Joseph Brant. Major Butler’s son Walter had overall command of the attack, and the famous Seneca chiefs, Little Beard and Cornplanter, were also involved. After the especially heinous slaughter of non-combatants in the town, the outcry for protection came from New York Governor George Clinton and its citizenry. General Washington had no choice but to act to secure possession of New York from the British. General John Sullivan and Brigadier General James Clinton (brother of the governor) were ordered to carry out Washington’s plan against the Iroquois nation.

SULLIVAN’S CAMPAIGN

Sullivan was in Easton, Pennsylvania, in May 1779 when he received General Washington’s letter outlining his orders. The following are excerpts from Washington’s lengthy letter to Sullivan dated May 31, 1779 (from the National Archives)

[Middlebrook, May 31 1779]

Sir,

…..

The expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the six nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.

So soon as your preparations are in sufficient forwardness, you will assemble your main body at Wyoming and proceed thence to Tioga, taking from that place the most direct and practicable route into the heart of the Indian settlements—You will establish such intermediate posts as you think necessary for the security of your communication and convoys, nor need I caution you, while you leave a sufficiency of men for their defence to take care to diminish your operating force as little as possible. A post at Tioga will be particularly necessary—either a stockade Fort or an intrenched camp—if the latter a blockhouse should be erected in the interior.

……

I need not urge the necessity of using every method in your power, to gain intelligence of the enemy’s strength motions and designs; nor need I suggest the extraordinary degree of vigilance and caution which will be necessary to guard against surprises from an adversary so secret desultory & rapid as the Indians.

….

After you have very thoroughly completed the destruction of their settlements; if the Indians should show a disposition for peace, I would have you to encourage it, on condition that they will give some decisive evidence of their sincerity by delivering up some of the principal instigators of their past hostility into our hands—Butler, Brandt, the most mischievous of the tories that have joined them or any other they may have in their power that we are interested to get into ours—

Now, Generals Sullivan and Clinton had to ready approximately 25% of the Continental Army, which was around 6,200 men, for what would be a scorched earth campaign against the Iroquois Confederacy. The soldiers in the Wyoming Valley area were now part of this campaign, and Moses became the quartermaster of the troops, responsible for all equipment, food, housing, and supplies for thousands of soldiers. In Van Campen’s biography, the beginning of the journey from Pennsylvania to Tioga Point was described as follows:

On July 31, Gen. Sullivan having completed his arrangements began to ascend the river from Wyoming toward Tioga Point. At the same time a fleet of boats under the command of Commodore John Morrison, sailed up the Susquehanna bearing in them the stores for the army. ‘His baggage occupied one hundred and twenty boats and two thousand horses, the former of which were arranged in regular order on the river and were propelled against the stream with setting poles, by solider, having a sufficient guard of troops to accompany them. The horses which carried the provisions for the daily subsistence of the troops, passed along the narrow path in single file, and formed a line extending about six miles.

The boats presented a beautiful appearance as they moved in order from their moorings, and as they passed the fort received a grand salute, which was returned by the loud cheers of the boatmen.’

The Sullivan Campaign lasted until October 1779, resulting in American atrocities upon the Iroquois nations. It was a campaign of retribution. Forty Indian villages were destroyed, hundreds of Iroquois were killed, including women and children, and thousands became starving refugees. Senecas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Mohawk peoples escaped to the British Fort Niagara for shelter and food. It was during this time that the Senecas tortured and murdered American soldiers Lieutenant Thomas Boyd and Sergeant Michael Parker. This infamous incident occurred in Little Beard’s Town (Cuylerville) as the Sullivan Campaign was in its last weeks. It was also Moses Van Campen’s first excursion into the Genesee country. Sullivan successfully completed his mission to decimate the Iroquois Confederacy in central and western New York, and Moses returned to Pennsylvania in September 1779, expecting safety at home. However, the war was far from over for Moses Van Campen.

COMING: PART TWO: VAN CAMPEN FAMILY TRAGEDY AND PRISONER OF WAR

Resources: mosesvancampen.com

Allegany County and Its People, John Minard

Sketches of Border Adventures in the Life and Times of Major Moses Van Campen, John Niles Hubbard

History of Columbia and Montour Counties, Pennsylvania, J. H. Battle

Wikipedia

One thought on “Moses Van Campen: Revolutionary War Hero and Pioneer in the Genesee Country”