A boulder on the Houghton University campus (formerly Houghton College) marks the final resting place of one of the Genesee’s legends, Copperhead. His identity was also disputed at one time, lending some mystery to this man who lived in the Houghton area for most of his life, but that has been resolved. To understand why Copperhead is important to Genesee Valley history, we need to back up to the Revolutionary War when the Senecas were part of the native coalition that supported the British army. General George Washington sent General John Sullivan and General James Clinton to carry out a brutal retaliation against the Iroquois Confederacy, which had carried out a scorched-earth campaign against the pioneer settlements of New York and Pennsylvania. The governor of New York begged Washington to send troops to save Americans, believing they would be wiped out if the Confederacy wasn’t stopped. Washington committed a quarter of the Continental Army to the campaign, which accomplished its mission in 1779 by destroying over 40 Native American villages and the inhabitants, vast quantities of corn, and other food supplies, driving survivors to the British stronghold, Fort Niagara, for protection. The Six-Nations Confederacy never recovered, and in 1797, Seneca chiefs signed the Treaty of Big Tree, selling over 3.5 million acres of the Genesee River Valley Region and land further west to the United States. The famous chiefs of the Senecas, Cornplanter, Red Jacket, Tall Chief, and Little Beard were among those who signed the treaty near Geneseo, New York. This event was also when Mary Jemison, the White Woman of the Genesee, received the Gardeau property. The Senecas kept tracts of land for themselves as reservations, and one of those was the Caneadea Reservation. It was a parcel two miles wide and eight miles long that began at the mouth of the Wiscoy Creek in the Town of Hume and continued along the Genesee River to Sand Hill Road and NYS Route 19.

In 1826, the Caneadea Reservation was sold to land speculators, and the small Seneca population moved to another reservation, except for one. Copperhead refused to leave “Ga-o-ya-de-o,” the Seneca word for “where the heavens rest upon the earth.”(Caneadea is an anglicized version of the Seneca.) He claimed that he hadn’t received payment for his lands and didn’t want to move from his home. With his land sold regardless of any compensation, Copperhead was homeless until a farmer kindly gave him land to erect a small cabin. It was located above the Bedford House near Old River Road and Centerville Road. There, he lived a peaceful life, hunting, fishing, and telling stories to neighborhood children.

Copperhead also became good friends with Charles Tarey, the constable in Caneadea. The Tarey family ensured the old man was supplied with fresh vegetables from their garden and checked on him daily. According to Grace Tarey, one of Charles and Lucy Tarey’s eight children who worked many years at the college, she remembered her father recounting the exploits of Copperhead. One of them was his estrangement from his tribe. In his youth, he’d been on a hunting trip with several men when the pony he was riding stumbled, and Copperhead went head-first into a tree. He awoke sometime later in a settler’s cabin and was kindly cared for by the couple until he recovered several weeks later. When he returned to his tribe, he learned of a raid against the white settlers and was conscience-stricken that the young family would be harmed. Copperhead slipped away to warn them, and when he watched the conflict from the bluff, he saw his tribesmen routed and killed. Later Copperhead was found out and excommunicated from the tribe. The story has some problems since he lived on the reservation before 1826 and was supposed to move to a reservation at the time of the sale. However, stories tend to morph over time, and this is likely one that began in fact but became partially fiction years later. Another claim by the old Seneca was that he was 120 years old near the time of his death.

The frail old man had no good heat source in his house and often went to a neighbor’s, lying on the floor by a woodstove at night to stay warm. The Bedfords and Tarey family were used to finding Copperhead asleep in their kitchen or parlor on cold mornings next to the stove. It was reported that the deed for the Bedford property included a clause to keep the back door unlocked for Copperhead to enter at night. This practice of lying close to a fire turned fatal in March 1864. On the morning of March 23, 1864, Charles Tarey checked on his neighbor and found him barely alive by the cabin’s fireplace. Copperhead was badly burned, the fire apparently spreading to his sleeping area on the floor. He died a few hours later. The Seneca authorities were notified and gave the neighbors instructions on a proper burial for him. Copperhead was buried in front of his cabin facing to the east with a kettle, some personal items, and his rifle in the grave.

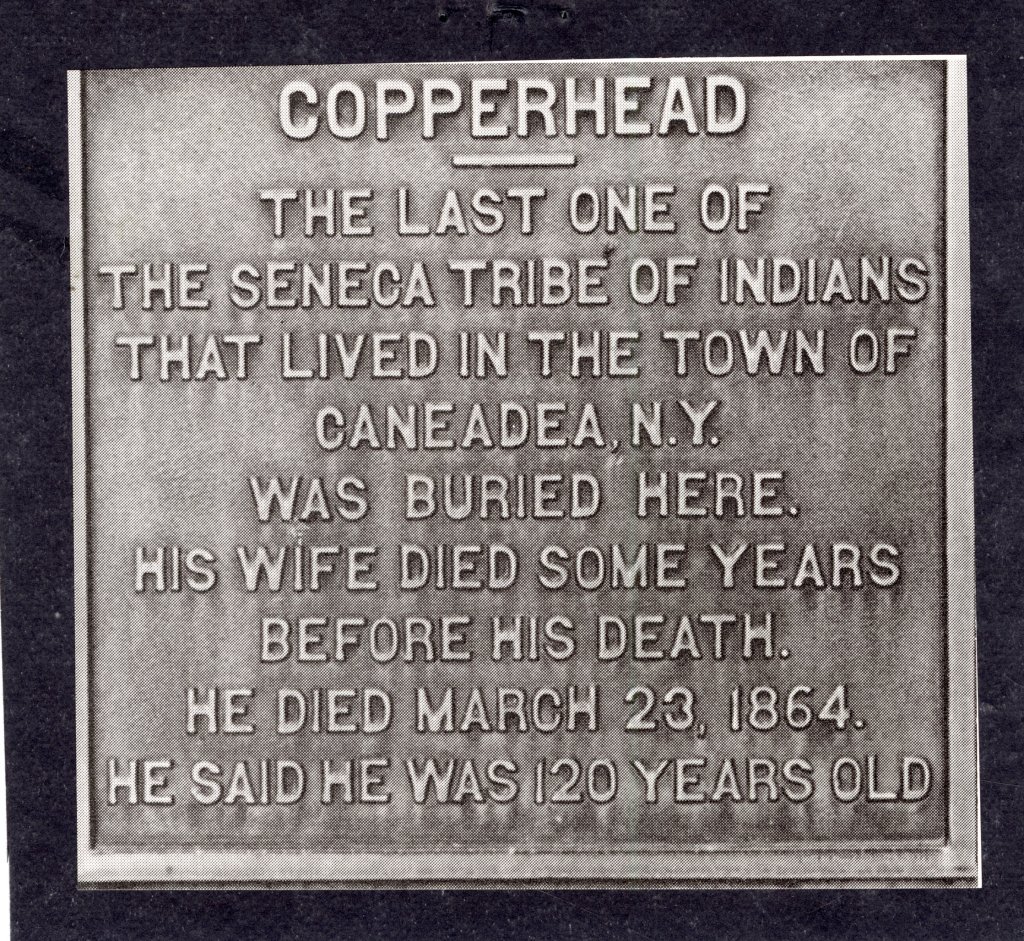

In 1910, Professor LaVay Fancher, who would later be Houghton College’s dean, expressed deep concern that a small creek had eroded the ground on the former cabin site and threatened to wash away the grave. In 1914, a group of students, faculty, and community members began planning the exhumation and reinternment of Copperhead’s remains to a safer place on the college campus. On June 10, 1914, two seminary students dug up the old grave and placed the bones in a metal casket, which were reburied during a solemn reinternment ceremony that evening. That fall, a boulder was brought from Houghton Creek by two teams of draft horses, hauled up the hill, and placed over Copperhead’s grave. A plaque taken from the old grave was installed on the boulder, which says, “Copperhead –The Last One of the Tribe of Seneca Indians That Lived in the Town of Caneada, N.Y. Was Buried Here. His Wife Died Some Years Before His Death. He Died March 23, 1864. He Said He Was 120 Years Old.” The boulder itself became the symbol of Houghton College’s yearbook, The Boulder. If you find yourself on the Houghton campus, the boulder and plaque are located at the top of Genesee Street diagonally from the Fancher Building, and you’ll know the story behind it all. A fitting memorial to legendary man.

Resources:

Houghton Star, 1910, 1914, 1952, 1998

Buffalo Courier Express, 1964

Olean Times, 1975

Allegany County Historical Society

National Archives, Washington’s Letter to Sullivan

Kelly Scrapbook 1914-1915, Houghton University Archives

Federal Census 1860

NYS Census 1892

History of Allegany County, John Minard